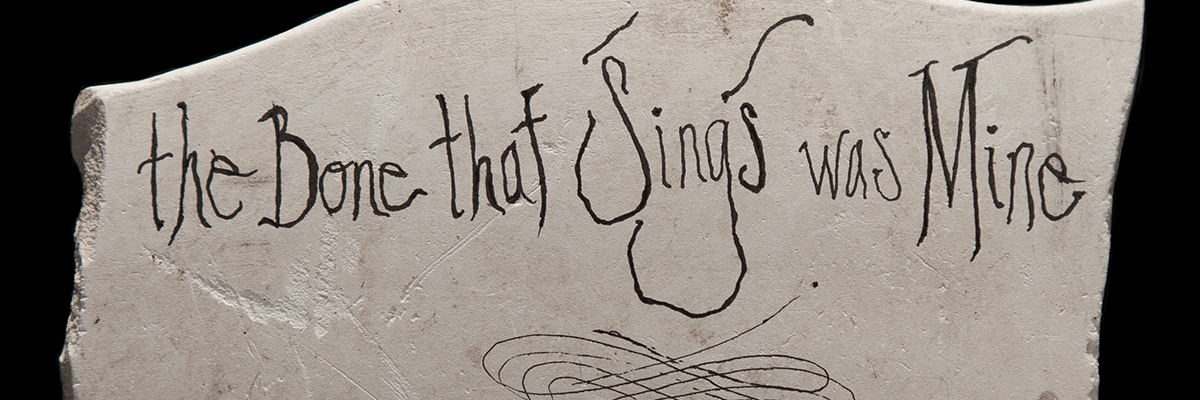

The Bone That Sings Was Mine

Curated By Defne Tutus

The Bone That Sings Was Mine presents nine artists whose work is deeply rooted in the body, transmogrifying bones and flesh as a way of giving physical form to treasure, myth and mortality.

among the bones you find on the beach

the one that sings was mine.1

The Bone That Sings Was Mine takes it’s name from a dissident poem by Lisel Mueller which broaches the question – who was I and what will I leave behind? The idiosyncratic, discordant and confusing experience of having a body and attempting to navigate the world is all preamble to this striving. We learn to tell stories, sing songs, make pictures and objects, and hope they capture the tone, the mood and the indescribable mixture of feelings we feel because we hope it will connect us to our fellows in this life. Likewise, we want to be known to each other, even after death.

The artists in The Bone That Sings Was Mine sew bones, repair and mend bits of trash, paint with hair and exuvia, make gold rust, fill a cemetery with mellifluous song. They make amulets, shields, masks, regalia, songs and storytelling that enchants. The nine artists in this exhibit leave behind objects, marks and sounds in the world that seek to express how strange it all was.

Evidence of the desire to surround oneself in death with objects both useful and protective, grave goods are buried with the dead in many cultures. Whether it’s a trinket or an elaborate panoply of riches, they buffet one for the vicissitudes of the afterlife. Combs and adornments to feel beautiful. A doll for a child who would cling to it for comfort. Masks, armor and shields to guard something human, since flesh needs no protection in death.

Kiki Smith once described making a plaster casting of her neighbor for her bronze sculptures before he had to get to work in the morning. The neighbor is late to work and rushes off, but his second body, a plaster skin coaxed from him by the artist, remains in the studio where it will begin a second life mostly unknown to the original body. Perhaps the Art Body will outlast both it’s model and architect.

The artist relishes the role of cajoling. It’s a shrewd act of devising and concocting a fictive, mirror skin from what we have access to – people, stories, information, objects. Whatever is familiar and mundane can be made rare and astonishing. A new world can be forged through sheer will and model building. The artist does not produce a simple document – an affidavit, a historical account. They’re spinning a yarn, rich with multivalent meanings, layered with fiction, spurred by the finite nature of our time here. The artist is not a reliable narrator. And the world is soft like mud.2 Answers glint on the surface for mere moments and sink out of reach almost as soon as we perceive them. Perhaps artists express the inexpressible, inexpressibly.3 And we want to be told stories because we need to dream before we sleep.

Notes

1.Lisel Mueller, Night Song

2.Elizabeth Wurtzel, Prozac Nation

3.Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts

Image

A broken pottery shard lies on a black background with the following written in a shaky hand: “The Bone that Sings was Mine.”

About the Artists

Yasmeen Abdallah makes stubborn relics out of refuse which simultaneously conceal and reveal their interior contents. These soft reliquaries to modern femininity insist upon a kind of sanctity, care and value. For more information on Yasmeen, visit her website and follow her on Instagram.

Christopher Baker’s obsession with the footnotes of history call attention to remarkable acts of resistance by people being violated by colonial settlers. For more information on Christopher, visit his website and follow his on Instagram.

Lauren Bradshaw’s work references death and decay, but retains a delicate vulnerability that ultimately suggests the resilience of their existence. Laruen’s work is seen here in collaboration with another artist, Theo Trotter. For more information on Lauren, visit her website and follow her on Instagram.

Katherine Earle’s tactile work is intricately woven, dyed and embroidered with materials of the natural world and its ecosystems. She explores what is left out of the stories we tell ourselves and she is invested in pushing back against the mythology of progress. For more information on Katherine, visit her website and follow her on Instagram.

Francisco echo Eraso’s work makes evident the construction of value through reproductions and allusions to the color gold, legacies of gold mining, alchemy, decadence, indigenous healing practices and capitalist accumulation. For more information on Francisco, visit his website and follow him on Instagram.

Christa Pratt’s work is concerned with perceptions of blackness, rituals of beauty and the embodied knowledge that is deeper and more layered than can be understood at a glance. For more information on Christa, visit their website and follow them on Instagram.

Miller Opie performs fantastical surgeries by stitching together bones and metal to produce chimera. Her magical bodies are equipped to defy the capricious nature of our human life. Her work is heresy against the tyranny of biology and elegant armor to the precariousness of flesh and blood. For more information on Miller, visit her website and follow her on Instagram.

Iván Sikic stages a delicate protest in a graveyard; an angry message sung softly in a familiar tune. Alongside mourners and visitors, he honors victims of femicide around the world in acknowledgement of the sad universality of violence against women. For more information on Iván, visit his website and follow him on Instagram.

Theo Trotter is drawn to creating elegant sculptures that “walk the thin line between beautiful and disgusting,” understanding that both can exist in one entity and can be both injurious and healing. For more information on Theo, visit his website and follow him on Instagram.